The tragic relationship between child poverty and homelessness in London

Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

The threat of homelessness is an extremely visceral fear. The lack of a safe place to sleep, eat, shelter from poor weather and gather with those closest to us should be a basic right that every individual sees realised. However, for thousands of children their home is just a hope. In the meantime, they might sleep in mouldy, cold rooms, while sometimes sharing a hotel bed with several siblings with nowhere to play or do homework.

At the end of February this year, the government released new statistics for July to September 2024 showing that 70,450 households in London are in Temporary Accommodation. Focusing exclusively on all households with children across the country in TA, 58% are in London alone. As Shelter, recently highlighted, 164,040 children are currently in TA and 92,850 or nearly 3 in 5 children in TA are in London. These children are not well captured in HBAI data, which is used to create child poverty statistics for the country. That could mean that nearly tens of thousands of children are missing from the estimated 700,000 children believed to be in poverty across the capital. We also know that children are being moved outside of their local borough or even outside of the city entirely, but we don’t know how many.

With the equivalent of one child in every classroom in London currently living in temporary accommodation, and 14,885 young people presenting as homeless to their local council across the city in 2023-24 figures, it is clear that all levels of government across London must take the intersection of the housing crisis and child poverty very seriously.

Gathered evidence shows that child poverty can be a predictor for adult homelessness and is almost always a co-existing reality for families facing the threat of homelessness.

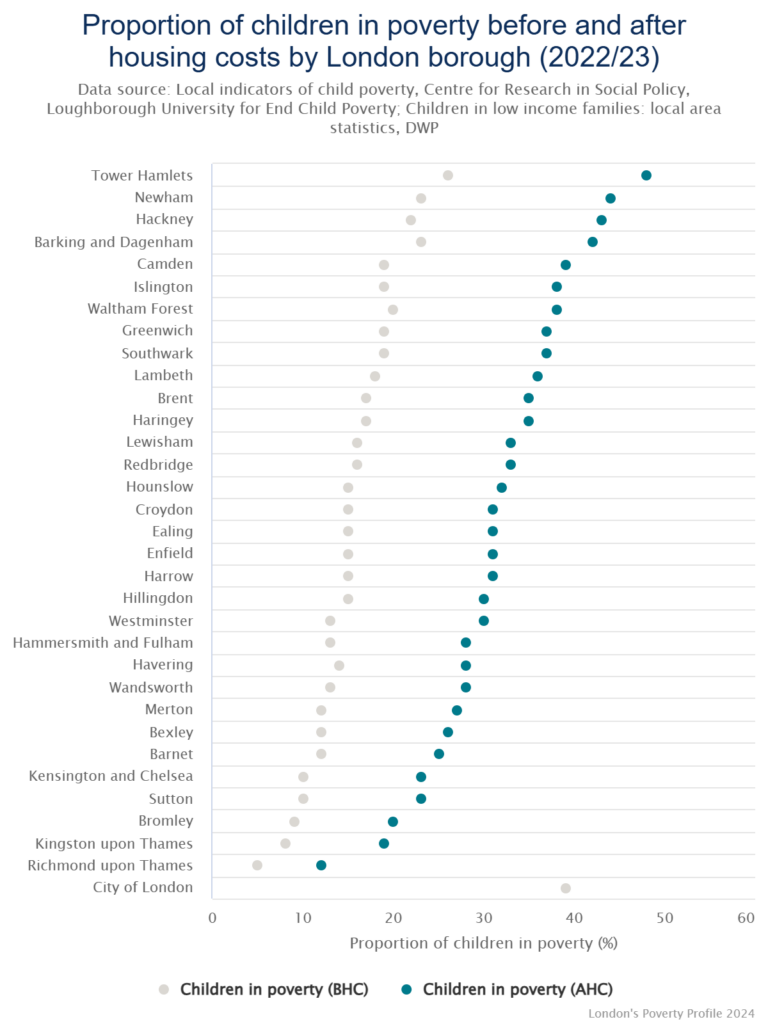

Trust for London’s 2022/23 data on child poverty rates after housing costs show significant jumps when housing costs are accounted for as the chart below shows. The affordable housing crisis in London and the hundreds of thousands of children experiencing poverty must be viewed in tandem. If we want to seriously prevent child poverty from causing long-term harm to children, we need to build appropriate, truly affordable homes fit for families who live in our community urgently.

The challenge though to quickly improve the lives of families is to provide the services they need when the threat of homelessness first looms. There are particular groups who face specific barriers when navigating personal crisis. For a parent who is threatened with domestic violence or a single parent with threats from debt collectors or joblessness due to unpaid caring responsibilities, holistic support is needed to help prevent and reduce the likelihood that they are unable to stay or move into a permanent home quickly. Other families are essentially forced into homelessness after their application for asylum is approved and they’re granted refugee status. These families often have little to no social and financial capital. Those still in a visa application process also face costly fees and limited social security support should they need it. And if a person has grown up in poverty and either loses their home or must leave their current place as a young person, their age may limit both their eligibility for support and prioritisation for what little help they can request.

Effective interventions must tackle both the broad supply challenges as well as the specific individual circumstances of Londoners. If change isn’t built on understanding of individual needs, it will fail to create systemic change.

Certainly, the evidence is clear that building more truly affordable social housing is the cure. At the same time, we also need to inoculate ourselves against the disease of child homelessness in London urgently. This is a public health crisis and a moral indictment.

We are currently leading a project focusing on the key moments when homelessness should and could be prevented. We believe that some crucial conversations need to be had about protecting families from homelessness and providing appropriate support to shorten or prevent experiences of homelessness. The issues are complex, but inaction is costly. Children have significant health, academic and social risks if we do not act quickly. We’re privileged to be working with Cardinal Hume Centre and New Horizon Youth on this project. Together we’re gaining insight from three particular groups to understand what policies need to be put in place while the houses are still being built.

We’re currently interviewing young people with experience of homelessness as a minor or young adult, migrant families and single parent, women led families. We are holding these interviews across March and April. If you know of someone who might like to take part, please do get in touch.

We aim to share our findings in summer 2025 and invite political leaders and civil servants to engage in important conversations about how we can support families to reduce the backlog of cases where families are living in unacceptable circumstances and children are growing up without a home.

Visit to Restorative Justice for All

One of the best parts of the role of community outreach officer for 4in10 is the privilege of being able to visit our extraordinary members and this has led to some truly fantastic experiences.

Whether it is being part of the series of campaign events put together by Southall Community Alliance, watching the presentation of new bleed control kits, donated by anti-knife crime charity Bin Knives, Save Lives or being part of community information events run by Poplar Harca housing association, this job continues to give me the chance to really experience the hard work of our incredible membership and has given me a real sense of hope.

Given this I thought it would be good to write about one of these events to give you a flavour of the experience.

A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to visit Restorative Justice for All (RJ4All)’s Rotherhithe Community Centre whilst they were doing their Wellbeing Circle.

RJ4All is a charitable international institute with a mission to address power abuse, conflict, and poverty through the use of restorative justice values and practices. The RJ4All Rotherhithe Community Centre serves as a vital hub for community empowerment and social connection at the local level.

As RJ4All’s Community Centre is always doing events, so for me it was originally more the date I was available to go than what activity I was going to be part of, but I was so glad I chose that day!

When I arrived, I was instantly made to feel completely welcome and shown around their centre. This was a very friendly building made up of a few side rooms, an office, a small kitchen and a small meeting room with sofas, tables, chairs and toys for children.

I was the first visitor to join but the session quickly filled up and by the time we were ready to go there were maybe 10 of us (all women). It was only at this point that I was grew to understand the nature of the event.

Our team leader explained to us that the idea was that each week the wellbeing circle explored a thought-provoking topic with the leader posing questions within it. She then apologised as it was her first week – not that you would have known she was brilliant.

I would not say I was cynical about the model – group therapy has been shown to do some amazing things but I was unsure how I would find it with not knowing anyone or indeed anything about the event but any anxieties I had were soon to be proved wrong.

The topic under discussion was ‘forgiveness’. First we were asked to explain in turn what we understood forgiveness to mean and then went on to explore times where we had each grappled with forgiveness.

As we went round the circle the comments of my fellow participants began to really touch something in me and as the evening went on I found myself talking about things and feeling emotions that I would never have thought about. And this, plus being with others while they explored sometimes very personal things profoundly touched me.

I came away from that extraordinary event feeling incredible, refreshed and if possible lighter; like I had been on a big therapy session. I would recommend this experience to anyone!

RJ4All’s Wellbeing Circles promote its overall vision of building the world’s first restorative justice postcode by providing a first line of mental wellness support to the community, strengthening relationships within the area, and fostering community cohesion in SE16.If anyone else would like to learn more about RJ4All you can go to their website here [I’ll include a link when it goes live].

'Make Childcare Make Sense' conference at City Hall (21 January 2025)

Last week, we were thrilled to host our ‘Make Childcare Make Sense’ conference at City Hall, generously hosted by London Assembly Member Marina Ahmad. This event marked the culmination of two years of dedicated work, focused on the challenges families on low incomes in London face when trying to access affordable childcare.

Last week, we were thrilled to host our ‘Make Childcare Make Sense’ conference at City Hall, generously hosted by London Assembly Member Marina Ahmad. This event marked the culmination of two years of dedicated work, focused on the challenges families on low incomes in London face when trying to access affordable childcare.

Our work was driven by an urgent and growing concern—raised both within and beyond our network—that the soaring cost of childcare is a key driver of child poverty in London, rivalled only by housing costs. In response, we partnered with our network members to investigate these experiences in depth. The findings are detailed in our report, Make Childcare Make Sense for Families on Low Incomes in London, published in March 2024.

The report revealed that the current childcare system is failing families. Many funding entitlements are inaccessible due to required ‘top-ups,’ inflexible policies that don’t accommodate diverse circumstances, and a lack of inclusivity for all children. Parents deeply value childcare, but they find the system frustratingly complex and overwhelmingly expensive.

These findings align closely with other key reports published around the same time, including the London Assembly Economy Committee’s Early Years Childcare in London and Business LDN’s No Kidding: How Transforming Childcare Can Boost the Economy.

Our event last week, which was attended by a wide range of stakeholders, took stock of the situation nearly a year on. We heard powerful contributions from members of the Childcare for All campaign group about their lived experiences of childcare when you have no recourse to public funds, from Single Parents Rights Network and KIDS, who support families with disabled children to access childcare. All had clear and very pragmatic suggestions about how the system could do much better to support the groups they represent.

Rosa Schling from On the Record delivered a fascinating presentation on historical childcare campaigns, including the National Child Care Campaign of 1985, which called for “comprehensive, flexible, free, and democratically controlled childcare facilities funded by the state.” It’s striking how closely this aligns with what the parents we spoke to today still need and want.

We also heard from Sarah Ronan of the Early Education and Childcare Coalition and June O’Sullivan from LEYF, both of whom made a compelling case for an urgent policy shift. They emphasized that while the Government is making significant investments in early years education, these investments are failing to reach the most disadvantaged children. Failing to address this is an untenable position for a government that is committed to both reducing child poverty and improving early childhood development.

Finally, we were delighted that Joanne McCartney, Deputy Mayor for Children and Families was able to attend and address the conference; to hear directly from families, practitioners and researchers about the current challenges and we look forward to continued dialogue with her and the Mayor about what the GLA can be doing to both support the childcare sector and families and children to benefit from it.

If you couldn’t join us last week, we truly missed you—and we can confidently say you missed out too! But don’t worry—you can still be part of the conversation. Watch our campaign film, where parents dare to dream of a future where childcare is accessible to all children, free and on an equal basis: https://4in10.org.uk/make-childcare-make-sense-a-4in10-film/.

Jobs from latest newsletter (24/01/25)

The latest jobs from our brilliant 4in10 members.

|

Government Holiday activities and food programme 2022

Holiday activities and food programme 2022 across London

The Government has provided local councils with some funding to allow them to fund free holiday childcare and food provision.

Full details about the program can be found here.

Around London each local council has spent the funding in different ways and supported different organisations so here at 4in10 we have attempted to gather them all together in one place.

Levelling Up White Paper: Why using London as a yardstick risks children everywhere

Levelling Up White Paper: Why using London as a yardstick risks children everywhere

In February, this year, the government released their long-awaited Levelling Up White Paper, a 300-page long publication covering everything from the history of the biggest cities in the world to twelve separate missions for the UK. By now, and a few months on from its publication, you may have read any number of analyses or opinion pieces on this unusual document.

At 4in10, London’s Child Poverty Network, amongst the myriad of missions and metrics, there were two key issues stand out as being of great concern:

- Child poverty in London is completely absent from the paper (the phrase ‘child poverty’ does not appear at all).

- London is used a yardstick for success for other regions, despite having the highest levels of inequality and poverty. The White Paper explicitly intends to replicate London’s economic model in other regions despite these facts. This risks the exacerbation of child poverty not just in London but in other areas identified as needing to be ‘Levelled Up’ (Middlesbrough, Blackpool, Newcastle, the Humber etc).

Child Poverty in London and Levelling Up

Although London is discussed in some sections of the Levelling Up White Paper, child poverty levels are not referenced. This is despite four in ten children in London currently living in poverty and nine of the ten local authorities with the highest levels of child poverty being located in London. If children in the capital, or elsewhere in the UK, are going hungry due to poverty – and the White Paper fails to mention – let alone address this – the phrase ‘Levelling-Up’ rings hollow. The White Paper does discuss the deprivation and lack of investment into many regions across the UK. However, it is possible for two truths to be present at once:

- Vast areas of the UK have experienced chronic underinvestment.

- London’s children are experiencing worsening poverty levels and increasingly deep levels of poverty.

It is true that some of London’s children do experience some advantages (but these tend to be limited to social mobility measures); a child on free school meals in London is twice as likely to attend university compared to those in the north of England. In London’s most deprived areas, nearly 90 per cent of secondary schools are either good or outstanding, compared with less than 50 per cent in deprived areas of the north. Transport spend per head has been higher in London for a decade (although this doesn’t always benefit poorer Londoners in outer boroughs); London transport spending per head was £864, compared with £379 in the north-west of England between 2009-2020. All of these facts are little compensation to the 12 children in a classroom of 30 who live in poverty in London. If one of the children in an East London classroom ends up going to Oxbridge, or gets a job at a top law firm, that is little compensation to the 11 others who still live in poverty. Similarly, the ability to get from Hackney (East London) to Thornton Heath (South West London), for as little as £1.65, means very little when the parent to the child pays (on average) £1,650 on rent per month in Hackney.

At 4in10, believe the Levelling Up agenda can, and should, address both regional underinvestment and child poverty rates in all areas of the country, including London. We should not pit children in one area against another (as the White Paper states itself; page xiv)– any child growing up in poverty in the United Kingdom is an avoidable tragedy.

There is a real risk that the high levels of poverty and child poverty, experienced in London and elsewhere, will be overlooked by national policy makers in light of the White Paper.

Replicating London’s Private Sector Productivity Model

“Typically, differences within UK regions or cities are larger than differences between regions on most performance metrics” (Levelling Up White Paper 2022: p27)

A significant part of the reason child poverty is overlooked by the Levelling Up White Paper is due to the fact the main objective of ‘Levelling Up’ is to reproduce the London’s levels of productivity in other regions of the UK, through processes of agglomeration. It is consistently implied, in the White Paper, that living standards will increase once the rest of the UK’s long standing productivity problems are resolved. In London, both as a whole unit and at local authority levels, productivity metrics are higher than other regions. Across the measures selected by the government as indicative of a productive area, Gross Value Added per hour, median gross weekly pay, and proportion of population with a Level 3+ qualification – London scores highly in comparison to other regions. This leaves London’s true picture of poverty somewhat obscured.

Using Gross Value Added (GVA), the favoured productivity measurement of the government, Tower Hamlets is the third most productive region in the country (ONS 2021). Therefore, Tower Hamlets has ‘Levelled Up’, right?

If you were to walk down in a street in Tower Hamlets, in the shadow of Canary Wharf, one in two families (55.8% – End Child Poverty Coalition: 2021) would be living in poverty; if you asked them how high GVA levels or the private sector productivity of the financial district has benefited them, they would struggle to give you an answer.

This gets to the heart of why we at 4in10 are alarmed that this model is being sought to be replicated elsewhere. Living standards, such as child poverty, in Tower Hamlets for example, would not be improved by a further increase in shiny new private sector buildings in the borough.

As a network organisation whose members have seen the impact of child poverty rising over the last decade, the use of London as a yardstick for success or model to be copied is highly concerning. It is not just concerning for children in London, but also for children in places like Leeds, Rotherham, and Middlesbrough, who are the primary focus of ‘Levelling Up’ narratives. Whilst ‘Levelling Up’ certainly means different things to different people, but we would all agree that an area has not levelled up whilst still having extremely high levels of child poverty.

The Equality Trust and New Economics Foundation have already flagged that the Levelling Up White Paper must focus on people, not just places. Research from the NPC (2022) shows that only 2% of the total levelling up funding is going on supporting social infrastructure so far, despite the public’s expectation that will Levelling Up tackle social issues. The public consider the most important aspects to an area being levelled up to be reduced homelessness (36%) and reduced poverty (36%).

However, the problems with the White Paper and child poverty levels in London run even deeper when contextualised against continuous unhelpful narratives:

How Can We Change The Narrative That London Doesn’t Need To Be Levelled Up?

After waiting a few months to see if these concerns would be addressed by policy makers, it is clear that we need an alternative narrative or frame to tell the true story of child poverty in London. Despite years of (sky) high child poverty rates in London, Westminster are simply not listening. No single statistic will provide a silver bullet to this problem, as:

- People outside of London either aren’t aware of the scale of child poverty in London, or they simply don’t believe the scale of inequality and poverty in London when presented with evidence.

- There is a sense of unfairness/grievance felt towards London from some parts of the UK; typically providing London with any public funding is unpopular.

- London is no longer a major political priority for either the national Conservative or national Labour parties

In light of these factors, we need urgently to find an alternative way to make the case for the 700,000 children living in poverty in the capital.

We want to work alongside our members, and anyone who shares our concerns about child poverty in London to help us tell the true story of its impact and challenge the prevailing narratives in the White Paper that prevent us from tackling it.

Cost of Living Crisis. URGENT action needed.

With the spring budget fast approaching 4in10 are calling on the Chancellor to uprate benefits in line with the Bank of England's February 2022 Monetary Policy Report forecast of 7% inflation.

We know this is not a solution to all poverty by any means and that there needs to be major changes to economic systems and social security in the longer term but it is what we can do to support many of our families now.

We have written to all our members and asked them to take action with tips for engaging local MP's and a sample email for adapting locally.

Please do feel free to use these to contact London MP's in time for them to understand how the cost of living crisis is impacting on their constituents from your experience.

A copy of the letter, tips for engagement and sample email are available here.

Proposals for a new Bill of Rights: what would it mean for children living in poverty in London?

Katherine Hill, 4in10’s Strategic Manager, takes us through the issues:

The story of Human Rights Act (HRA) reform has been a long and somewhat torturous one. Governments of various guises have been consulting on what changes might be needed since the mid-2000s, only a few years after the Act came into force. While the content of these proposals has changed over time the one constant has been that those who have made the effort to respond diligently to each round of consultation have almost unanimously concluded that there is no solid case for reform; the Act is doing the job it was intended to do, effectively defending ordinary citizens against the exercise of excess power or neglect by the state.

Most recently the Independent Human Rights Act Review (IHRAR) set up by the Government to take (yet) another look at the Human Rights Act reported that, “[t]he vast majority of submissions received by IHRAR spoke strongly in support of the HRA.” And the separate but concurrently running inquiry carried out by the cross-party Joint Committee on Human Rights concluded: “[t]o amend the Human Rights Act would be a huge risk to our constitutional settlement and to the enforcement of our rights”. Why, then, has the Government now published proposals for wide-ranging and significant changes to the way the Act works? We all know that evidence-based policy is out of fashion, but this seems to have gone one step further. It is embracing policy in that is in direct contradiction with the evidence. This is policy driven by ideology pure and simple.

At this, the temptation may be to throw up our hands and leave the beleaguered Human Rights Act to the hands of fate. What is the point of repeatedly making the case for it, only to be ignored? There are two reasons. Firstly, we must recognise that the case for effective human rights is one that needs to be constantly remade, it will never be a case of job done. Human rights, if they are to mean anything, must be a statement of collective values, an expression of our shared commitment to freedom, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy for all humans. For these to be transmitted from generation to generation there needs to be ongoing dialogue about them and what they mean in our modern world. Shying away from that conversation leaves the legal mechanisms we have for defending our rights vulnerable to attack.

Secondly, and more pragmatically, if we do not argue and win the case for the Human Rights Act, and these current proposals for reform come into force, ordinary citizens may lose the means to enforce their rights effectively. For those 4in10 exists to advocate with and for, families and children experiencing living in poverty in London, the consequences are potentially very serious indeed.

The proposed reforms aim in multiple ways to make it harder for people to enforce their rights. These include a proposal to introduce of a new step in the legal process requiring individuals to demonstrate that they had experienced “a significant disadvantage” before their case can go to court. Legal action can already only be taken if the individual is the “victim” of a human rights breach, so it is hard to view this as anything other than an attempt to deter people from enforcing their rights by adding a further legal hurdle to the process. This will disproportionately affect those experiencing poverty who are more likely to have their rights breached in the first place. To give just one example, children in the lowest income quintile are 4.5 times more likely to experience severe mental health problems than those in the highest.[1] It follows that some of those are more likely to experience mental health detention too, where their human rights – including the right to respect for private and family life (article 8) and right to liberty and security (article 5) – will be engaged. If children in these circumstances, who already find it very difficult to access justice, have to jump through additional hoops it will further diminish their ability to challenge their detention where they believe it is an unlawful breach of their human rights.

The Government’s proposals would introduce a two-tier system for enforcing human rights by restricting their use in the domestic courts by certain groups, including “foreign criminals” and those accused of illegal migration. This makes a mockery of the values underlying the whole notion of human rights. These are rights that everyone is entitled to enjoy regardless of economic or immigration status, gender, sexuality, disability or anything else. It follows that all should have equal access to the law to enforce them. If they don’t, the impact will be felt most by those on the margins, and especially the poorest children in our society. If the Government is more easily able to deport people without them being able to challenge this on the grounds of right to respect for private and family life (article 8), families may face the sudden loss of their main breadwinner, and children living in already financially precarious situations will be plunged into deeper poverty.

A key issue the Government seeks to address through its plans is that it wants to stop what is termed ‘judicial overreach’, that is the courts getting involved in decisions that are more properly the role of Government and Parliament, accountable as they are to the people. High on the list of things the Government believes it is best placed to make decisions about is the allocation of social and economic resources and it is particularly aggrieved when it thinks the courts seek to interfere in these issues.

The reality is however, that there is little evidence that this is what the courts in the UK are routinely doing. Recent cases that have examined welfare policy have often been unsuccessful, for example a challenge to the two-child limit (which does not allow welfare payments to be made to third and subsequent children) on the grounds that it discriminates against lone parents. The courts found these to be matters on which Parliament has deliberated and struck an appropriate balance. This may be very disappointing for those of us who believe that there should be a wider role for human rights in these matters, and that the right to an adequate income, a safe and warm home and access to healthy food meet basic human needs that should be enforceable whatever the colour of government in town. But it certainly does not support the Government’s argument for the need to curtail the powers of the courts, and the rights of individuals, as is proposed.

Over the longer-term we need to build the case and argue robustly for more comprehensive protection of these important economic, social and cultural in our domestic legal framework, as an essential element of any strategy to eradicate poverty. But first, and most urgently, we need to protect what we already have in the form of the Human Rights Act, as failing to do so will have the greatest impact on those who most need to rely on it.

To find out more about the Government’s plans to reform the Human Rights Act and to find out how you can respond to the consultation visit the British Institute of Human Rights dedicated web pages where you can find lots of easily digestible information and advice.

[1] Gutman, L., Joshi, H., Parsonage, M., & Schoon, I. (2015). Children of the new century: Mental health findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. London: Centre for Mental Health.

Human Rights Perspective on 'Levelling Up'

4in10 sees poverty as an abuse of human rights. As Nelson Mandela put it:

'Overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice. It is the protection of a fundamental human right, the right to dignity and a decent life. While poverty persists, there is no true freedom.'

Equally Ours have published an excellent, evidence based report written by Belinda Pratten, Levelling Up: Firm Foundations.

Written from an equalities and human rights perspective it covers work, social security, social care, civil society and housing as well as the wider issues of public procurement and investment. A great Christmas holiday read.

Universal Credit Cut. A Letter to MP's

Sutton Voluntary Sector have sent a jointly signed letter to their MP's to detail exactly what the cut to Universal Credit will mean locally. They have suggested sharing it for anyone to adapt to their locality. Thank you to Steve from Sutton CAB for this:

Dear MP's Name

Universal Credit

As you will recall, we have previously exchanged correspondence and had a useful meeting about the ending of the Universal Credit Coronavirus uplift. Over the last few weeks, there has been a lot of media coverage and commentary about the issue. There is a lot of concern among staff and volunteers in Sutton voluntary sector organisations about how the ending of the uplift will impact on Sutton residents. I am writing on behalf of the Sutton voluntary sector organisations listed at the bottom of this letter. We all have concerns about the £20.00 per week reduction in Universal Credit; concerns that recently have been exacerbated by the impending increases in fuel costs and food price inflation.

We would be grateful if you would consider asking the government to reconsider its decision to end the uplift. We hope that the information below, about the impact of the reduction in Sutton and the Universal Credit regulations will be helpful to you.

There were, according to official DWP figures, 15,493 Sutton households ‘on’ Universal Credit as of May 2021..

The government increased the Universal Credit ‘standard allowances’ in 2020 in response to the Coronavirus pandemic. A monthly ‘standard allowance’ is included in the calculation of every UC claim. There are different standard allowances for people for single people, couples and people under and over the age 25. The standard allowances are, as you can see from this table, quite low.

| Standard Allowance | Current Rate | Rate from 6th October 2021 |

| Single under 25 | £344 | £257.33 |

| Single 25 and over | £411.51 | £324.84 |

| Couple under 25 | £490.60 | £403.93 |

| Couple aged 25 or over | £596.58 | £509.91 |

We can illustrate the impact of the Universal Credit reduction with an example calculation. The client is an illustration, but the calculation is based on actual Universal Credit amounts.

The claimant is a lone parent with one daughter aged 14. Her current ‘maximum amount’ of UC for is £694.01 per month (plus housing costs). This maximum amount is comprised of the £411.51 standard allowance and the Child Amount of £282.50.

The claimant works part time. She earns £520 per month (net). The calculation of her UC includes a ‘work allowance.’ She can earn £293 per month without her UC being reduced. She has earnings of £227 over her work allowance. Every £1.00 of earnings over the work allowance reduces Universal Credit by £0.63 – i.e., earnings ‘taper’ UC entitlement at 63%.

The calculation of her UC entitlement compares her maximum UC - £694.01 (plus housing costs) with her income. She is treated as having income of £143.01 (63% of net earnings minus the work allowance). She is therefore entitled to UC of £551 per month, plus housing costs. Child Benefit is paid in addition to Universal Credit.

From 6th October, the claimants maximum Universal Credit is £607.34. This is comprised of £324.84 standard allowance and Child Amount of £282.50. She will then be entitled to UC of £464.33 (plus housing costs). This is a reduction of £86.67 per month.

As you can see from this example, Universal Credit is reduced by £0.63 for every £1.00 of earnings over the work allowance. Only people responsible for a child or people with a limited capability for work have a work allowance. Other people such as those without dependent children and carers (who do not otherwise qualify) do not have a work allowance.

Most claimants cannot therefore make up the £86.67 per month shortfall by working additional hours. If the claimant in the above example increased her working hours and therefore her net pay by £86.00 per month, she would lose £54.18 from her Universal Credit, meaning that she would, despite earning £86 more per month, only gain £31.82 per month - so the claimant can clearly not make up the £86 per month reduction in benefit by earning an additional £86 per month.

Many people in receipt of Universal Credit do not have any realistic way of making up for the £86 per month reduction at all. Some 60% of people in receipt of Universal Credit are not in employment. People may for example have a limited capability for work, be caring for a severely disabled child or adult or be a lone parent with a young child. Some people in receipt of Universal Credit are working full time (and need the benefit to help with rent), so cannot further increase hours and therefore cannot, in any way, make up the reduction. We would like to stress, that even if people can increase their earnings, those earnings will reduce Universal Credit by £0.63 for every £1.00 of earnings.

You can see, from the above table, that the Universal Credit standard allowances are quite modest. The standard allowances are the basic entitlements for single people or couples. Although these allowances are not designed to cover rent or council tax and claimants may also receive amounts for children, caring responsibilities and having a ‘limited capability for work- and work-related activity,’ the amounts are very low when compared to the ‘Standard Financial Statement’ ‘Trigger figures.’

Debt advisers, such as the Citizens Advice Sutton debt team use a Standard Financial Statement. The Standard Financial Statement includes ‘trigger figures’ The trigger figures are pre-agreed levels for certain areas of discretionary household expenditure. The trigger figures help identify levels of monthly expenditure deemed reasonable when completing the statement. Debt advisers do not need to explain the financial statement to creditors unless the trigger figures are exceeded.

The Universal Credit amounts are inadequate to allow claimants even the trigger figure amounts of discretionary expenditure. The Standard Financial Statement ‘allows’ a single adult to spend a total of £666 per month on ‘discretionary’ items – communications / leisure and groceries etc. However, the Universal Credit Standard Allowance for a single adult (over 25) is currently only £411.51 per month and is due to decrease to only £324.84 per month.

The Standard Financial Statement ‘allows’ a single adult with a dependent child to spend a total of £885 per month on ‘discretionary’ items. However, a single parent with one child could receive Universal Credit of no more than £648.59 per month (due to decrease to only £562.92 per month) plus Child Benefit of £21.15 per week. Even including Child Benefit, the family’s income would total only £740.24 per month, decreasing to only £654.57 per month in October.

Furthermore, many people in receipt of Universal Credit have a shortfall between their rent and the amount of housing costs included in their UC calculation – the Local Housing Allowance only covers the 30th percentile of local rents.

A very high proportion of Citizens Advice Sutton debt advice clients are in receipt of Universal Credit and have a ‘deficit budget’ – in other words, their incomes are inadequate to cover even essential expenditure such as rent, utilities and food.

We understand that the government introduced the £20 per week uplift as a temporary measure, in response to the pandemic. However, many people need to claim Universal Credit for the long term. As we have said above approximately 40% of Universal Credit claimants are in employment and need Universal Credit to help pay rent. Many of these people have not seen any improvement in their situation since the introduction of the uplift – in fact their financial positions may have deteriorated due to rising food costs and will deteriorate further with increases in fuel costs. The Citizens Advice Sutton debt team has seen an increase in demand in recent months.

We hope that this information is helpful to you. We would be grateful if you would ask the government to reconsider their decision to end the Universal Credit uplift – a decision that will have significant adverse financial consequences for over 15,000 London Borough of Sutton households.

Yours sincerely